A Sprint Through 4,000 Years of Local History

The Prehistoric Men and the Teutons – Saxon and Frankish Tribes

Human history in the area around Hattingen dates back to the Neolithic period. Archaeological discoveries prove, that parts of todays Holthausen, Welper and the western hillside of the Isenberg have been inhabited since 2000 BC. Within this time the so called “Hilinciweg” or “Kleiner Hellweg” has most likely already been a pathway through the Balkhauser Tal and the Bergisch region to the bays around Cologne.

A Germanic cult site: the “Horkenstein”

During the first centuries AD a germanic tribe called the Hattuarians inhabited the central areas of the Ruhr. There, a small settlement emerged from the river banks: “Hathneghen” - named after the hillside “Nocken”, above the rivers ford. This little settlement became the foundation of Hattingen, as we know it today.

In

the 8th century, the Saxon tribes claimed the Ruhr-area and it

became the Saxon gau (region/district) “Hatterun”. After Emperor Charlemagne

subjugated the saxons in the early 9th century, the old Hattuarian

settlement evolved into an imperial Franconian court, whose 20 aulic farmyards

spread through the whole countryside - from Elfringhausen to Stüter and

Stiepel. The region around Hattingen was of strategic significance to the

Franconian empire, as it controlled the Hillinciweg, the fords of the river

Ruhr and was close to the Frankish border.

The court Hattingen and its church were gifted to the newly founded Benedictine abbey in Deutz near Cologne by the future emperor Heinrich II in 1005. “Hattingen” is mentioned the first time in 1019/20, when archbishop Heribert of Cologne accepts the emperor’s gift. In 1147, the church of Niederwenigern is also listed as his property.

Isenberg - A Murderers Tale

At the end of the 12th century, archbishop Adolf of Cologne and his brother Arnold of Altena constructed a massive fortress on the Isenberg. Shortly after, the power structures in the region changed drastically: On November 7th in 1225, Burggrave Friedrich of Isenberg ordered his men to capture archbishop Engelbert of Cologne. The captivation failed, the archbishop was accidentally killed.

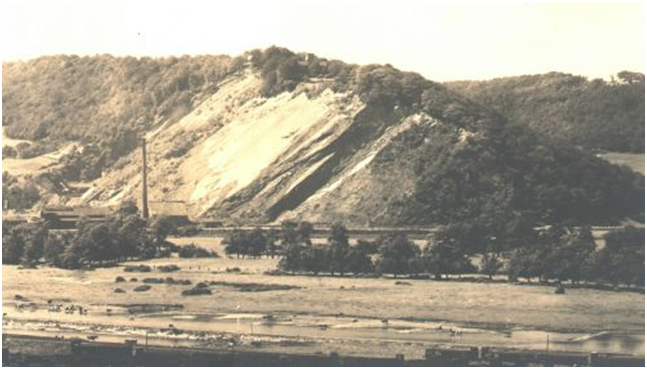

Isenberg

with the remains of the Isenburg

Thereupon Friedrich was executed in Cologne and the Isenburg destroyed. The new sovereigns of the Hattingen region, “die Grafen von der Mark” chose the “Blanken Steyn” (the bare rock) as the new location for their keep. As Hattingen and its church were still in the archbishop’s possession, the village rapidly found itself in severe distress. Soon, a personal vendetta between the archbishop and the sovereigns turned into a bloody battle for power; in 1250 and 1254, Märkisch soldiers loyal to Bernd Bitter, the steward of Blankenstein burned Hattingen to the ground. Even after the court of Hattingen desperately begged the Count von der Mark to become their patron, the village stayed endangered: On April 2nd 1263, mercenaries burned Hattingen to ashes as an act of vengeance by the archbishop.

A Growing City

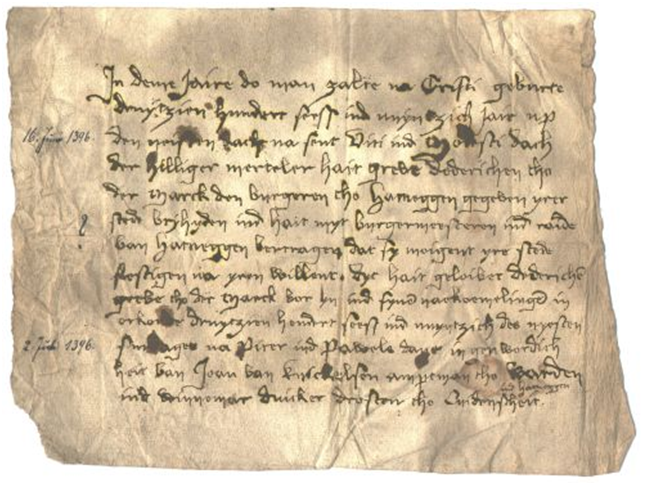

Since Hattingen turned out to be the border to County Berg and was in constant danger from the menacing Archbishop of Cologne, the village gained certain privileges by Count von der Mark throughout the years. This was to ensure the peasants’ contentment, hold military presence and to secure the advantageous outpost economically. But as the privileges came one by one, the process of becoming a city stretched to almost one hundred years. On May 17th in 1350, Count Engelbert gave Hattingen minor civil liberties, the so called “Freiheit”. But at the same time, Hattingen had already established a market and the mayors and council started first attempts of self-administration. Nevertheless, only when Hattingen gained the privilege to fortify its town with city walls by Count Dietrich von der Mark on July 2nd in 1396, Hattingen was officially recognised as a city.

Report

of the presentation of municipal law

Report

of the presentation of municipal law

All following privileges, including travelling tolls, taxes on wine and grain, market rights and duty exemptions were added to the municipal law of Hattingen. In 1486, the mayors and the city council were given the privilege to pass their own laws and statutes. With these new possibilities for self-administration, Hattingen completed the transformation to a prospering medieval city.

At the same time, the cottages and farms in the countryside gathered in so called “Bauerschaften”, farming communities, which later evolved into local communities. The settlement below castle Blankenstein was given minor civil liberties in 1355 as well. Like Hattingen, it was governed by mayors and a council.

Economic Upturn

The formation of three guilds in 1412 turned Hattingen into the most important trade centre in the western County Mark. Drapers in Hattingen gained extreme supra-regional importance. Even though the city was burned down during the war between the two brothers Count Adolf and Gerhard von der Mark in 1424, the cities’ economy increased enormously: Soon, merchants from Hattingen visited international markets all over Europe. Hattingen and Blankenstein officially joined the Hanseatic League in 1554. The cities’ prosperity can even be admired today - most of the half timbered houses in the Altstadt (city centre), like the richly ornamented city hall from 1576, are still standing.

The old city hall

The Protestant Reformation spread to Hattingen and the surrounding area around the year 1580. This initiated the cities’ detachment from the catholic church and from the monastery Deutz - which provoked many conflicts in the upcoming century.

Only Blankenstein and Niederwenigern remained as catholic communities. From the 17th century and onwards, this religious structure in the Hattingen area remained unchanged.

War and the Black Death

As military conflicts and the menacing Black Death reached Hattingen in the 17th and 18th century, the cities’ prosperity and economy crumbled. As a result of the war of the Jülich Succession, Hattingen and the County Mark belonged to the Electorate of Brandenburg from 1666 onward.

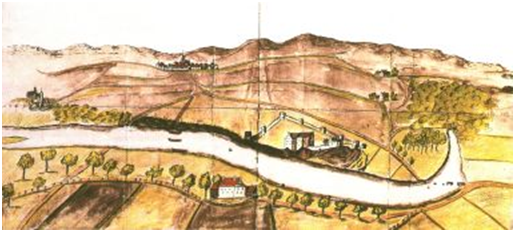

Hattingen around 1660

The devastating Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) took a toll on the region, from which Hattingen was only able to recover slowly. When the textile and mining industry became more and more lucrative, the region needed new methods of transport for the massive load of products. As the river Ruhr became a navigable waterway in 1780, the Hattingen region was connected to a net of economic centres. Industrial traffic moved away from the rather poorly developed roads onto the river, which formed the base for the industrialisation of the Ruhrgebiet.

From 1815 onwards, just after the foreign rule of Napoleon Bonaparte, the offices of mayor of Hattingen and Blankenstein were reorganised to resemble the French administrative system. They were also affilated to the District of Bochum, which was situated in the newly founded Prussian Province Westfalia.

Count Henrich Changes the Region

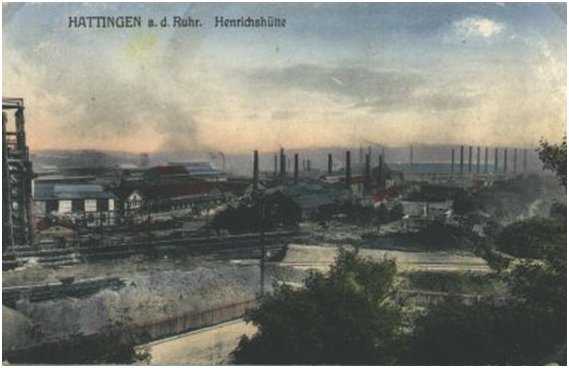

In the middle of the 19th century, the textile industry rapidly grew irrelevant. The drapers in Hattingen simply forgot to keep up with modern industry standards. But luckily, there was a substitute: Miners found the mineral Siderite. This iron ore made way for heavy industry in Hattingen. In 1853, Count Henrich zu Stolberg-Wernigerode bought 76 Morgens of land from Bruch Manor in Welper, to build a steel mill. The region’s next 130 years were shaped by the so called “Henrichshütte”: The steel mill dominated the economic and social structure of the whole region. Especially Welper experiences a time of significant economic and population growth.

Henrichshütte

Hattingen started to expand beyond the old city walls. In 1869, the city was connected to the railway network. Streets like the “Bahnhofstraße” grew drastically and developed into a public service and administration area. Since then, administrative offices like the district of Hattingen (1885), the main office Hattingen-Land and the local court, the local post office and multiple bank premises, but also the new catholic church St. Peter und Paul (1870) and a synagogue (1872) were constructed there.

With the new city hall built in 1910 on the so called “Pastorskamp”, the city expanded even further, getting closer to the premises of the Henrichshütte. All surrounding streets remind of the Wilhelmine era, being named Bismarckstraße, Roonstraße, Augustastraße or Victoriastraße.

Dark Times

The end of the First World War marked the beginning of a turbulent time for Hattingen. From 1923 to 1925, the Ruhr-area was seized by French and Belgian troops to ensure proper payment of reparations from the war-torn Germany.

French troops marching through Bruchstraße.

Not only this occupation, which was considered to be a cruel injustice by the population of Hattingen, but also the enormous economic crisis, inflation and unemployment rate caused political radicalisation in the city. This made Hattingen become a stronghold for the right wing Hitler party NSDAP and the left wing Socialist party KPD. During the early 30s, the results of this radicalisation included bloody street fights and fierce political debates on a daily basis. Tensions in the population were increased, when communal reorganisation led to the dissolution of the District of Hattingen and the creation of the “Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis” in 1929.

The National Socialist parties’ rise to power in 1933 affected the Hattingen region exactly like the rest of Germany: Opponents of the regime were intimidated, suppressed, arrested and terminated.

NS-Youth event in the protestant parish hall

In the so called „Reichskristallnacht“ (Crystal Night) in the night of November 9-10 in 1938, the Nazis burned down the synagogue at the Bahnhofstraße and scavenged jewish homes and businesses.

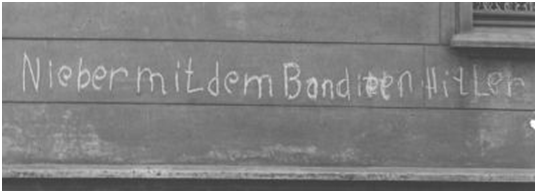

Resistance, November 1939: Down with the bandit Hitler!

WWII brings nothing but suffering and destruction.

More than 10,000 prisoners of war and forced labour workers abducted from all over Europe were brought to Hattingen, being forced to work in “important” factories for the war - the working and living conditions in the designated ca. 100 barracks were often cruel and inhumane.

Most of the jews that lived in Hattingen before the war started have been deported to concentration camps in 1942, where they were tortured, brutalised and slaughtered.

During the last months of the war, the citizens of Hattingen experienced the true meaning of “Total War”: Most of the time they had to flee into bunkers and air-raid shelters, fearing for their homes and lives. Parts of the old town centre in Hattingen, Welper and Blankenstein were bombed and destroyed in two large-scale attacks in March 1945. More than 1000 men of the Hattingen region never returned from the battlefields.

Upwards

After being liberated by American troops on April 16th 1945, the citizens of Hattingen directly started rebuilding their city. A lot of people had lost their home during the war, food supplies and building materials were scarce. Only a fortunate circumstance had stopped the disassembly of the Henrichshütte and saved an economic foundation for the reconstruction. Another repercussion of WWII: Hattingen had to give shelter to a massive amount of refugees. In 1962, almost 10,000 refugees lived in the city, being 30% of the population. Suburbs in the south of Hattingen and the Rauendahl were plucked out of thin air. An economic miracle!

Reconstruction

For the next decades, the Henrichshütte (with its capacity to employ 10,000 workers) shaped the region once more. To build a sintering plant, the Henrichshütte even funded the relocation of the river Ruhr in 1959. Plans to reorganise the Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis concretised in the mid 60s. To prevent their annexation to Hattingen, Blankenstein, Buchholz, Holthausen and Welper united as the Stadt Blankenstein; a city founded in 1966 which lasted only four years.

A new Hattingen

The first of January 1970 marked the beginning of a new era. After intense discussions, the communal reorganisation founded a newer, bigger Stadt Hattingen, consisting of the former city Hattingen, most of Blankenstein and Bredenscheid-Stüter, Niederelfringhausen, Oberelfringhausen, Oberstüter, Winz. The new municipal area spread over 71 qkm with 60,490 inhabitants.

The “Altstadtsanierung”, an expensive renovation project for the buildings in the city centre (Altstadt) which already started in the 1960s, were continued. These renovations proved to be a long-term future investment and had a significant influence on the city image. Thousand of visitors still admire the around 200 protected half timbered houses in Hattingen today.

The 80s will be remembered as a decade of structural change and industrial disputes: The two biggest factories in Hattingen were at the brink of ruin. Thousands of workers of the flange and bearing factory Mönninghoff/Gottwald and those of the Henrichshütte fought for their factories and jobs. These battles were not only fought on the factory grounds or in conference rooms, but on the streets of Hattingen as well. When the Henrichshütte closed down on the 18th of December 1987, the morale of the whole city seemed broken: Has Hattingen become a dying “steel city”?

Hattingen fights for their steel industry

Even after all those setbacks, there was no time for resignation. Work had to be done, the structural change had to be managed! The first achievements turned out to be remarkable: Modern factories and businesses settled down in the newly build nature and business-park at the old factory grounds of the Henrichshütte. New industrial districts were developed in Ludwigstal and Am Beul. Now focusing on medicine, the slogan „Med in Hattingen“ made Hattingen a renowned centre for health and wellbeing in the adjacent regions.

Hattingen developed into a city full of museums as well. “Westfälisches Industriemuseum Henrichshütte” (Industrial museum of the Henrichshütte), “Westfälisches Feuerwehrmuseum (Firefighters museum) and the Stadtmuseum in Blankenstein are just a few of the many museums in the Hattingen region, which become more and more popular every year.

With the “Reschop-Carré“ shopping centre being opened in 2009 and the cities’ marketing process being intensified, the city is well prepared for what lies ahead.

Reschop-Carré

Working together, the city and its inhabitants developed an urban development concept for Hattingen in 2030, which includes interesting new perspectives for each part of the city.

Es gibt viel für Hattingen zu tun, packen wir es gemeinsam an!

(There is a lot to do for Hattingen, so let us get to it!)

© Thomas Weiß, Stadtarchivar Translation by Benedikt Weiß Stadtarchiv Hattingen 2021 Alle Rechte vorbehalten